And why rent payments are so important

Last year, we published an article about how much affordable housing costs to develop. As a follow-up to that post, I’ll cover a related topic here: the cost of operating an affordable housing project. Every month, affordable housing owners must pay a variety of costs to keep a building running, and ultimately, keep the people within it housed. If we don’t pay these costs, the building risks falling into disrepair or missing mortgage payments.

Because paying for building operations relies on rent, consistent rent payments are critical to a functioning affordable housing system. The importance of reliable rent payments recently became an issue in the District of Columbia, where, after a large surge in nonpayment of rent after pandemic-era eviction reforms, nearly half of DC’s income-restricted subsidized housing became at risk of foreclosure. This forced DC to redirect the majority of its housing production trust fund, a program created to produce new affordable housing, to bail out existing properties instead. Fortunately, the recently passed RENTAL Act in DC includes some commonsense reforms in response to this issue that will hopefully help the city’s affordable housing providers continue operations.

Operational costs also influence the level of subsidy required to provide affordable housing. If operational costs increase, there isn’t as much cash flow to support regular mortgage payments. Just like personal homeowners depend on an income to qualify for a mortgage, the size of the loan developers can get is directly proportional to how much cash flow the building will generate to go towards mortgage payments. Greater operating costs means lower cash flow and, therefore, lower debt. To make up for this, governments can either A) provide more capital subsidies to make up for the reduction in the mortgage or B) increase operational subsidies to the property (e.g. with tenant vouchers) to provide cash flow great enough to support a larger mortgage.

So how much are these important operational expenses and what do they pay for? Below I provide some averages from a subset of True Ground properties. For the sake of comparability, all these properties are elevator-served apartments with underground parking that opened relatively recently in Arlington County, VA.[1]

Rent and Operating Expenses Summary

| Basic Income Statement | Monthly (per-unit) | Annually (per-unit) |

|---|---|---|

| Rent | $1,715* | $20,580* |

| Operating Expenses | -$847 | -$10,160 |

| Capital Reserves | -$25 | -$300 |

| Mortgage Payment | -$703** | -$8,436** |

| Remaining Cashflow | $140 | $1,684 |

*60% AMI 1-bedroom rent cap for Arlington County (Novogradac). Net rent amount assuming $130/month utility allowances.

**Sized at a 1.20 debt service coverage ratio

Rent — $1,715 per unit per month

In exchange for federal, state, and local capital subsidies that we receive to build affordable housing, the government limits the rent we can charge. This rent ranges based on the metropolitan area, the bedroom type, and income limit (usually measured as area median income – AMI) of the unit. A fairly typical unit type is a 60% AMI 1-bedroom unit, which in the DC region in 2025 is capped at around $1,715/month. This rent is the main revenue source for operating the unit.

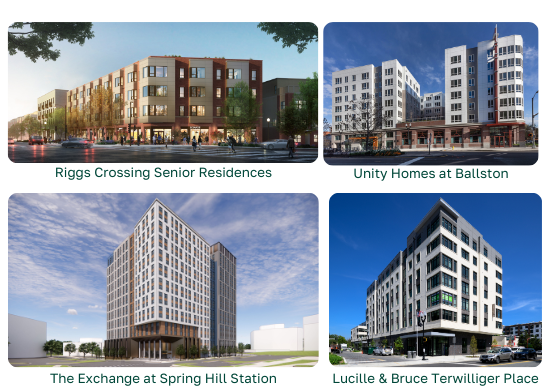

Operating Expenses — $847 per unit per month

The bulk of operational costs go towards maintaining, insuring, and managing day-to-day operations of the building. We usually group these costs into a few main subcategories shown below:

Major operating expenses categories ($ per unit per month).

- Payroll for Property Staff ($211 per unit per month): Each building includes dedicated property management staff, who manage day-to-day operations such as leasing, rent payments, resident packages, compliance with government regulations, financial reporting, and move-ins or move-outs. There is also typically a dedicated maintenance engineer onsite for repairs. These are hard jobs that require technical expertise, project management, and high-quality customer service. The property operating budget pays for their salaries and benefits.

- Taxes & Insurance ($206 per unit per month): Property taxes, general liability insurance, and other insurance required by lenders. Property insurance rates for multifamily apartments have dramatically increased in the past 5-10 years nationwide, becoming one of the largest annual expenses. Similarly, property taxes are a sizeable cost. In some places, income-restricted affordable housing gets preferential property tax treatment. This can greatly reduce the amount of subsidy required for the project, as property taxes usually amount to 10% or more of operational costs. Montgomery County, MD has a popular Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) program where affordable housing developers can abate most of the property taxes in exchange for income-restricted units. In France, meanwhile, most social housing developers are exempt from property taxes for the first 15 years, which contributes to their high rates of social housing production.

- Maintenance and Cleaning ($165 per unit per month): The costs of maintenance supplies and labor for regular maintenance of the building. Things like carpets, elevators, doors and windows, HVAC, and plumbing systems need regular cleaning and maintenance. This also includes the contract costs for janitorial services, landscaping, and trash services. Unlike single family homes, most localities do not provide public trash and recycling services for multifamily properties, which are forced to use 3rd party contractors.

- Administrative Expenses ($148 per unit per month): Office supplies, accounting and legal fees for compliance with funding programs, and marketing costs for leasing. This also includes a percentage fee paid to the property management company for their overhead costs.

- Utilities ($116 per unit per month): Cost of electricity, gas, water and sewer services for all the common areas of building (lobby, community spaces, fitness room, etc.). We pay standard rates to receive these services from publicly available utility companies, and so are subject to increased utility costs like anyone other property owner. In most cases, residents pay these costs for their individual units, although we are required to reduce their rents by a pre-determined amount (known as a utility allowance) for this.

Capital Reserves — $25 per unit per month

In addition to regular operating expenses, lenders typically require that properties set aside money every year to save for regular capital improvements over time. This is wise, as buildings need to eventually replace building systems as they age. The amounts of reserve contributions can vary by property type, but a typical amount is $25 per-unit per-month escalating at 3% per year.

Mortgage payments — $703 per unit per month

After property operations, owners need to pay the mortgage for the commercial loan used to build the project. These loans come from large banks and are sized according to the rent and operating expenses expected from the property. To mitigate risk, banks carefully assess the project and only lend if there is projected to be enough leftover cash after operating expenses to comfortably cover their mortgage payments. Typically, a standard lending rule is for the property to have enough cash flow after operating expenses to cover 120% of the monthly mortgage payments. This is shown in the table above at $703/month. As developers, it makes sense to leverage the maximum loan amount allowed by lenders, because this minimizes the number of other capital subsidies needed to build the project.

Remaining Cashflow — $140 per unit per month

After paying for required operating expenses, capital reserves, and mortgage payments, the remaining cash flow is small. In our example above, of the original $1,715/month in rent collected, only about $140 (~8%) is leftover after necessary expenses. This remaining cash flow is then usually split 50/50 between the building owner and local governments to repay their housing trust fund loans. All things considered, subsidized affordable housing is essentially operated at cost.

The table and costs described above emphasize why regular rent collections are such an essential component to a functioning affordable housing system. If even a small portion of units are vacant or a few residents skip paying rent, property owners may be forced to cut back on essential operating expenses, such as maintenance or management payroll. If not, they risk missing mortgage payments and facing foreclosure, which can wipe out affordability requirements, meaning the community loses committed affordable homes.

This thought exercise also shows why it’s so difficult to reduce rents below certain levels without additional government subsidy. The most common rent level in the LIHTC program, 60% AMI, is just enough to cover the typical operating costs of a modern apartment building with the typical levels of government capital subsidies. To lower rents even further to 50% or 30% AMI levels, rents don’t cover operating expenses, so more subsidies are needed. These can come either through capital subsidies that reduce the overall mortgage amount needed or through operating subsidies (e.g. rental vouchers) that make up for the lower rents.

[1] These averages come from a sample of seven projects built between 2012 and 2024. For more information about the sample, feel free to contact me directly at [email protected].

About the author: Brian Goggin is a Project and Policy Manager on True Ground’s Real Estate Team.