A rough guide based on DC-area projects

Zoning reform, simply making it legal to build more housing in more places, is a necessary part of digging ourselves out of an historic affordable housing shortage. But lowering development costs to make it financially feasible to build more affordable housing is perhaps an equally important part of the solution. By taking a closer look at how much it costs to build, we can start to have a more well-informed discussion on the possible levers and the tradeoffs involved. The Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley has a wonderful series on the costs of building housing in California on their website. In this spirit, I thought it’d be worthwhile to share a little about the development costs we experience at True Ground.

The charts below present some average costs from a sample of 10 True Ground housing projects in the DC area. These projects were all built or started construction sometime between 2013 and 2025.[1] Before delving in, a few caveats. First, the costs below are from projects recently built in the DC metropolitan area, a high-cost market that is not representative of the whole country. Second, for the sake of comparability, the projects for this exercise are all ground-up new construction buildings with underground parking, a common feature for new buildings in the inner-ring suburbs of DC.

While this sample isn’t representative of affordable housing overall, it’s a good data point, especially considering high-cost markets like DC area are also where there are the most acute housing supply shortages. These costs can also teach us some important lessons about how to more efficiently use scarce subsidies to produce affordable housing – resulting in more units per dollar spent! This is especially important given increasingly strained budgets at the federal, state, and local levels.

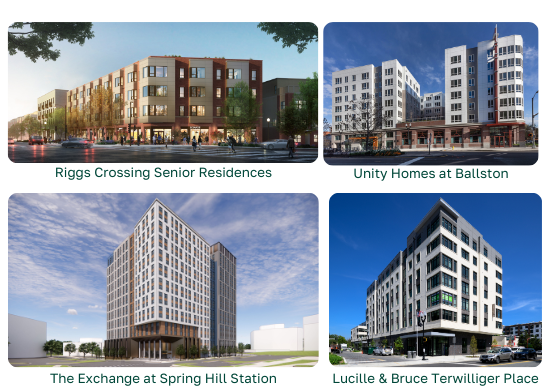

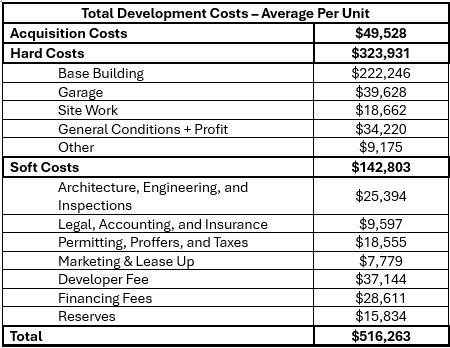

Total Development Costs

On average, it costs a little over half a million dollars ($516,263) to build one unit of affordable housing from this sample of projects. This total is composed of three broad subcategories of cost:

- Hard Costs ($323,931): The contract amount paid to the general contractor for the labor and materials to construct the building.

- Soft Costs ($142,803): A broad set of costs related to designing, permitting, marketing, and financing the building.

- Acquisition Costs ($49,528): The cost to acquire (in most cases, purchase outright, in some cases ground lease) the land for building.

Acquisition costs are self-explanatory, but let’s explore the hard and soft cost categories in more detail.

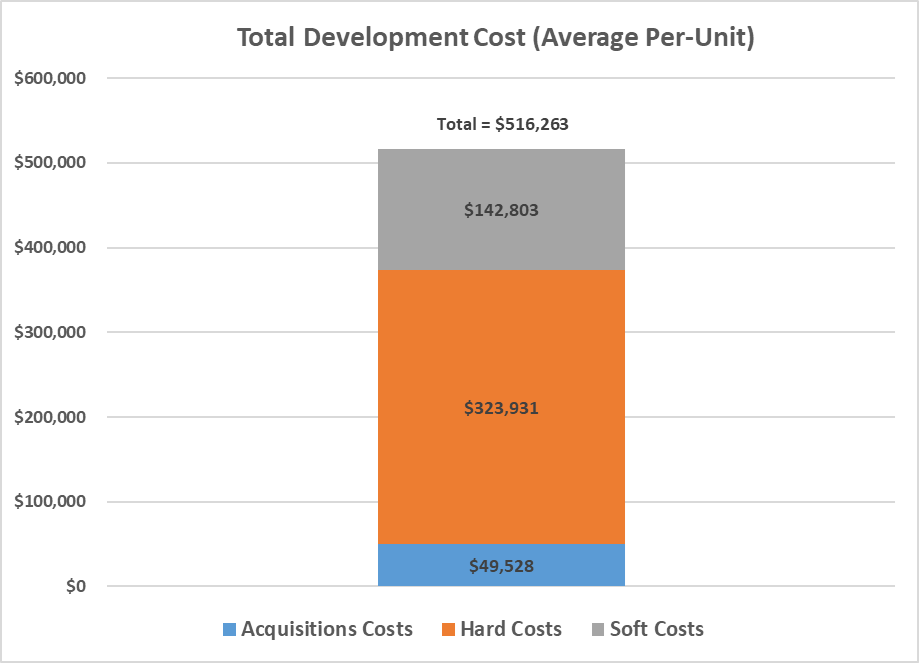

Hard Costs

Hard costs, the costs required to construct the building, are the largest driver of development costs. Buildings are extremely complex and require the work of hundreds of different skilled trades all under the coordination of a general contractor. The industry does have a standard set of costs, known as CSI divisions, which divide costs into a set of 50 universally-accepted divisions. For the sake of this simplicity, I’ve chosen a different, broader set of subcategories in the chart above:

- Base Building ($222,246): The cost of materials and labor for the subcontractors responsible for constructing the building. This includes a broad range of trades, such as foundation work, framing, concrete, masonry, metals, wood & plastics, plumbing, etc.

- Garage ($39,628): The costs of building an underground parking garage in the building (i.e. additional excavation and concrete). It’s not always typical to track this cost separately, but the projects in my sample here track this due to Virginia Housing tax credit rules.

- Site Work ($18,662): The costs of preparing the site for pre-and-post construction. This includes excavation, building new or relocating existing utility lines, physically moving dirt to prepare for the building foundations, new pavement around the building, and landscaping.

- General Conditions + Profit ($34,220): Overhead and profit for the general contractor, who is contracted to lead the construction work. The general contractor coordinates the work of all the subcontractors on site and communicates any issues or progress updates with the owner and architects throughout construction.

- Other ($9,175): Miscellaneous other fees, such as commercial liability insurance fees, taxes, and bond fees paid by the general contractor.

Together, hard costs make up about 60% of total development costs, and so any significant effort make development cheaper at scale will have to reckon with how to lower these costs. One obvious local policy fix that can help is lowering or removing minimum parking requirements. Over 10% of the hard costs above are for building underground parking. This usually always translates into seven-figure cost changes that can make or break a development project. I have personally worked on a project saved by flexibility on these parking minimums in Arlington. Nationally, dozens of localities (e.g. Minneapolis) have eliminated parking to the effect of sharp increases in housing production.

On a federal level, wage requirements attached to federal funding can also dramatically raise costs. Although I haven’t broken them out separately, two of the projects in the sample above include federal funding that requires prevailing wage rates per the Davis-Bacon Act. These projects have almost 30% higher base building costs than the rest of the sample. Although these wage requirements might be a worthwhile labor policy goal for federal funding, the tradeoff in reduced affordable housing production is very real.

Beyond this, reducing hard costs is hard, complicated work. Construction costs have consistently outpaced inflation for the past 100 years, and there’s some evidence that stagnating labor productivity is a major cause. Reducing these costs will take the hard work of both increased hiring in the construction sector combined with innovation in existing building practices. Immigrants comprise a large portion of the construction labor force. As the country experiences impacts from immigration enforcement, as well as implementation of tariffs on building materials, costs are expected to increase. Personally, I’m also excited about the potential of low-hanging fruit from building code reforms (e.g. elevator cost reform) that lower costs by bringing us more up to date with international best practices.

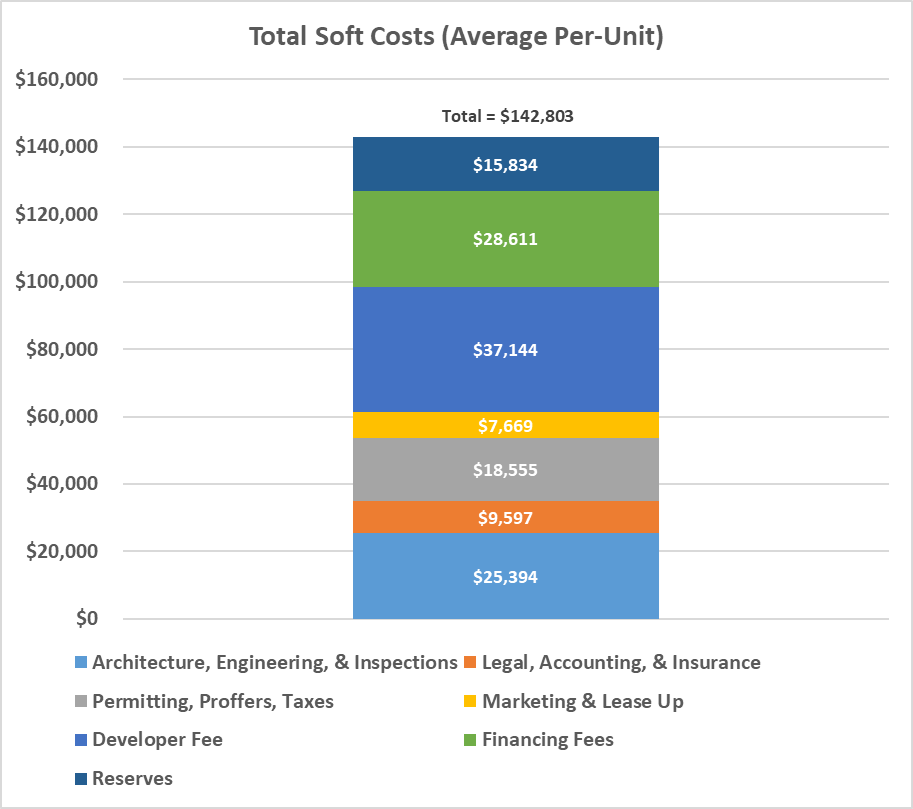

Soft Costs

Soft costs are the “everything-else-other-than-construction” costs. The wide variety of costs here reflect the complexity of real estate development and the range of subject-matter specialists involved. In the chart above, I decided to group soft costs into several basic sub-categories:

- Architecture, Engineering, & Inspections ($25,394): This category includes architecture costs for designing the building and supervising the design during construction. It also includes several engineering disciplines – civil, structural, mechanical – involved in the design. As a developer, True Ground doesn’t have in-house design or construction expertise, so we typically hire a third-party construction manager to review materials from the design team, which is included here. Also included here are regular inspections of the materials during construction. Finally, I included the cost of purchasing furniture for the common areas of the building (typically a few thousand dollars per unit) here.

- Legal, Accounting, & Insurance ($9,597): This includes legal fees for negotiating all of the transaction documents (e.g. purchase and sale contract, loan documents, etc.). It also includes accounting fees for preparing cost certifications for tax documents. Third, it includes insurance covering the building materials (called builder’s risk insurance) as well as general liability insurance for during the construction process.

- Permitting, Proffers, & Taxes ($18,555): This includes building permit review fees from the locality. It also includes proffer requirements, additional required fees added by the locality through the development review process to mitigate the impacts of the development. These can vary widely, from new streetlights and bike racks to replanting trees and even public art contributions. I am also including permitting-related consultant fees, such as traffic or environmental impact consultants (often required to complete studies during zoning approval) in this category. Finally, this category includes property taxes due during construction.

- Marketing & Lease up Costs ($7,669): This includes the costs of appraisals and market studies needed for tax credit or financing applications. It also includes costs for marketing the building during lease-up. Finally, some projects include betterments, such additional maintenance materials or backup supplies, at the end of a project when there are excess funds. I’ve included those here.

- Developer Fee ($37,144): The fee paid to the developer (in this case, True Ground), to pay staff that manages the project. This helps pay dozens of staff (development project managers, asset managers, accountants, etc.) that touch the project over its lifecycle. It also gets recycled to fund feasibility studies and design for future affordable housing projects (what we call “predevelopment funding”). Additionally, 30%-50% of this fee is typically deferred by True Ground and re-invested in the project.

- Financing Fees ($28,611): Fees paid to the lenders and investors who finance the project for their review and underwriting. Each project typically has between 5-10 separate sources of financing and they each have their own review process. This category also includes the interest paid on the construction loans during the building process.

- Reserves ($15,834): It is standard practice to fund up-front reserves for operating, lease-up, and replacement expenses at the time a building opens. These reserves help keep the building running in case there are leasing issues and help fund occasional maintenance over time.

There are so many components to soft costs that it’s hard to pinpoint any one category as a silver bullet for reducing overall costs. But it’s worth mentioning a few general drivers of cost across multiple categories above.

The first is financing complexity. Because of our fragmented system of funding affordable housing, each project typically has 5-10 funding sources for each project. This typically includes a combination of private investment from a LIHTC investor, permanent loans and construction loans from a private banks, and additional loans low-interest loans from state and local governments. Each one of these financing sources comes with its own set of conditions, timing, and legal documents that may or may not overlap nicely with the others. Coordinating these different sources to fund a project takes enormous amounts of staff time and legal review, not to mention separate financing fees for every source. Putting a precise estimate on these added costs is difficult, but research on affordable housing in California from the Terner Center suggests it could be as high as $6,500/unit for each additional funding source added. One way to reduce these costs is for state, local, and private lenders coordinate program requirements and timing in advance.

A second driver of costs, not unique to affordable housing, is zoning uncertainty. Like most American cities, localities in the DC area ban apartment-building on most of their land area. And where it is legal to build, it usually requires extensive zoning review and public hearings that can take anywhere from months to years to complete. This review process, known in the planning world as “discretionary review”, adds significant design, legal, and staff costs by requiring multiple design changes. Zoning laws are often extremely complex and require a specialized land use counsel to guide developers through the zoning approval process. Zoning more land for apartments “by right” with simplified, standardized rules, could help reduce costs substantially.

That’s it for now! Hopefully these charts can give you a helpful mental map of the cost components of affordable housing and their rough size. To conclude, below is a table with all the cost categories mentioned above. And to all pro-housing allies, consider raising cost reform in your next advocacy meeting.

[1] Eight of these projects are in Arlington County, VA, one is in Fairfax County, VA, and another is in Washington, DC. Various assumptions were made in creating standardized cost categories across projects.

About the author: Brian Goggin is a Project and Policy Manager on True Ground’s Real Estate Team.